Share this Collection

1 Citation in this Annotation:

Annotated by:

Jaehee Shin on Spacegirls her här her

11 October, 2023

“The task for feminism is thus both to uncover forgotten aspects of history and to change structures and patterns that have been repeated for generations.”

Fanny Söderbäck, Revolutionary Time, 2019.

The book ‘her här her‘, edited by Magdalena Rozenberg, is an eclectic treatment of the Spacegirls‘s work, using texts and interviews from a wide range of people to shed light on the complex implications of their work. I would like to reflect on the meaning of how they work and the results they achieve, from a personal point of view: the ways in which this young female duo redefines, reinterprets and realizes the reality given to us in our time; and how they challenge it through different experiments with a complex attitude in physical and non-physical way.

This is relevant to the Women Writing Architecture project because each of these three separate words is connected to Spacegirls’ practice, not loosely, but strongly.

*

Architecture, which has so closely been linked to the economy and time, is also indirectly influenced by education, but it’s much harder to escape its shadow in practice. As Rudolf Schwarz wrote in his book <Wegweisung der Technik>, if something of a certain quality is built over and over again, then ordinary people have affordable and generally good quality spaces to be in. This notion of repetition has been a virtue addressed throughout human history and it has been very influential architecture, but in principally as efficient way to reduce construction cost and time. In this schema, architecture with artistic pretensions still has a role and meaning, but for architects acting against the huge impetus towards efficiency, it has been, perhaps, not easy.

The challenge of this uneasy journey is brought to life through Spacegirls’ projects, and their book, with a consistency full of conscious choices with clear intentions. And it is presented with an attitude that accurately and beautifully connects many of the questions we face in our time. The very perceptive and sensitive aesthetic consistency and constructive attitude contrasts with the funky xoxo_spacegirls name on Instagram, which I find fascination. Since the name Spacegirls refers to the duo, it feels like the beginning of their practice was more about their identity as young women than as architects. Their project is one of the few significant works that brings all together many of the feminist attitudes that are currently widely discussed and translates their complexity into tangible practice.

In order to broaden this discourse, from the early planning stages onwards, they not only separate their experiments with materials from the constructive project of building (an actual pavilion), but also plan their writing and publications as independent projects. Those who have been invited to contribute to the publication by Spacegirls and editor Magdalena Rozenberg, who themselves are pushing their own feminist boundaries both within and outside of architecture, are carefully selected. The contributors directly refer to the issues either in dialogue with Spacegirls, or they indirectly touch upon the Spacegirls’ project and its implications, allowing for multiple perspectives. In addition, the Spacegirls keep a photographic and diary-like journal of the project’s progression, from recording the emotions they experienced at each stage of their decision-making to the moments they question their decisions, giving the reader a direct link to the multitude of emotions they face as female architects.

The fact that the publication is not written in a single style, but uses a variety of media, is written in several neighbouring Scandinavian languages, and is heavily annotated with important glossaries and citations to help guide the reader through the project, shows that the women do not exist in an isolated way. It feels a little different from the usual monograph, which is full of one architect’s architectural attitudes, architectural journeys, and architectural positions. Surprisingly, Spacegirls refuses to put the spotlight solely on their own project. Rather, the book is a practical exposition of various existing discourses, but at the same time, it wants to bring them together and convey all their old interests to someone. It does not exist alone, but together.

*

I’m a little wary of listing the ways in which composite complex and eclectic attitudes were practiced in a project like an anatomy, because I know that they are very powerful when they come together, and it’s very difficult to completely reconstruct the conceptual and methodological framework that underpins them in detail.

Refusing the definition of an age-old word

This female duo rejects the long-accepted definition of the terms architecture and architect in society. The unquestioned definition of a word creates boundaries and discourages attempts at something different. They respond very closely to the current social currents that demand new definitions of complex and changing terms, such as annotations and glossaries. They use words like practice, work, or the result of labour, and create their own balance in the middle ground where new insights, processes, and methods can be discovered.

Creating community

They find clues in unfamiliar frames outside of art or architecture that define their practice, and they create community bottles by speaking in terms of the many, not the I, we. Produced in an interdisciplinary way and using a mix of media, the book allows for interaction and feedback with people who are working in their own fields while still being self-aware of their feminist attitudes.

Ambiguity – situational, contextual and spacial

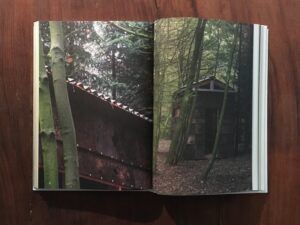

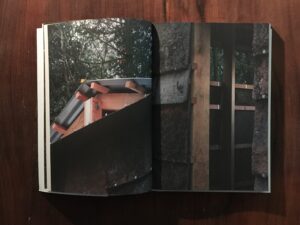

Spacegirls’ work is ambiguous in many ways, a word that perhaps connects us to Analogue Architecture, which has a longstanding place in Swiss architecture. It’s an architecture that connects to a typologist’s memory, where past and present are linked, but in a very subtle way that evokes newness. In their work, however, ambiguity is present in the choice of sites for their monumental gentle pavilions, the contextual concepts within which their projects are developed, and the reinterpretation of those concepts as they are physically interpreted.

Aesthetics of inefficiency

In their project GHHS, they challenge the grand architectural aesthetic attitude of mass production, which focuses on uniform and smooth surfaces, by attempting to produce a 100% analog self-production. Using the body’s muscles and bones as tools, the aesthetic effect of imperfect production through human error is reminiscent of the moon jar, which they say is the most aesthetically pleasing piece of Korean ceramics.

“Do you think it might be possible to create a machine-based mass production that focuses on diversity instead of product uniformity?”

Spacegirls

Questioning the authenticity of a value system defined by science and numbers

“The ochre doesn’t make the concrete mix magically better, but it doesn’t make it much worse either… Normally, an experiment is meant to confirm or disprove, but ours doesn’t seem to want to be captured in a numerical system… However, the focus of our studies has been more on the sensory and non-quantifiable aspects of the material. Aspects that are often overlooked in data-orientated, technical materials research. There’s no doubt that concrete is an interesting and efficient material.”

Spacegirls

Relation between architectural thought and text.

Although there is an oral form of architectural criticism in studio classes and in connection with reviews of student projects, architecture students are rarely encouraged to think about the relationship between thought and text; the relationship between the way we understand the world and a written form of representation.

Oldest coffee pot in Denmark

Denmark’s oldest coffee pot. The jug, from around 1680, is made of Arita porcelain. it’s functional and decorative, both ornamental and textural. In the book

In The Four Elements of Architecture (1851), Gottfried Semper describes the hearth as a central point, one of the four basic elements of architecture. Perhaps the coffee pot can be our hearth. A kind of heart in architecture that collects and releases heat?

Scandinavian languages

Together with Spacesgirls, the editors have invited writers from Norway, Sweden, and Denmark to write in their native languages. A multilingual publication that recognizes the uniqueness of the languages of the Scandinavian countries, reinforces their interconnectedness, and expands linguistic horizons is certainly unusual.

*

I underlined and read follow three key glossaries repeatedly – Coexistence, Heterogeneity, and Stranger, which are written in Marja Zander’s text “Picker Places and Hospitality” in this book. These three words are being discussed under contemporary feminism and linked to the Spacegirls’ project keenly, but not yet seen as one of the important values in architecture education and practice. These might be very close glossaries to the urgent architectural issue of sustainability.

공존 coexistence

“All are dependent, or formed and sustained in relationships where they depend or are depended on. What each individual depends on and what that depends on each individual varies, as it is not just other human lives that are at stake, but about other senses, environments and infrastructures: We depend on them, and they in turn depend on us to maintain a livable world.”

Judith Butler, The power of nonviolence, 2020.

이질성 Heterogeneity

“Space is not a container for a finalised system in which everything is already connected, but rather a field of possible temporal-spatial constitutions that may or may not manifest themselves. We should therefore not imagine the place as a predefined space in which something can take place, but rather a multitude of continuous spatial formations, relational events that are constantly created by the situations that constitute them.”

Doreen Massey, For Space, 2005.

낯선 자 Stranger

“O my soul, be prepared for the coming of the Stranger, Be prepared for him who knows how to ask questions.”

Eliot, T.S., The Complete Poems and Plays, 1969.

The stranger is someone who, by virtue of their outside perspective, can question what we take for granted. Someone who can make us see ourselves from the outside, see ourselves and the world through the eyes of the stranger.