Testing Oral History

Helen Thomas

This collection reflects the term ‘oral history’ in the Women Writing Architecture bibliography, testing it to see what the boundaries of this idea on the website are. Not all the texts included here come under that term, but each one gives it sense.

Searching using the word ‘speak’ and extending what this could mean (the personal voice, speaking in diaries and journals, for example) was especially interesting because it brought citations to the list that, while not belonging to oral history in the strict sense, gave the concept an unexpected depth.

Dates

Texts and Annotations from 1010 to 2021

Themes

Construction

Critique

Domesticity

Environmentalism

Feminism

Food

For children

Gender

Life work

Oral history

Shared space

Spectra

Travel

Ways of feeling

Ways of thinking

Publication Types

Book

Book chapter

Catalogue

Diary

Essay

Manuscript

Online article

Podcast

Authors

Anna Funder

Annebella Pollen

Annemarie Burckhardt

Araceli Tinajero

Beate Schnitter

Deborah van der Plaat

Dorothy Wordsworth

Elizabeth Burnet

Flora Tristan

Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak

Jane Drew

Janina Gosseye

Julia Gamolina

Kirsten Grimstad

Kirsty Bell

Laurence Cossé

Linda Martín Alcoff

Lisa Robertson

Lucia Berlin

Maria Graham

Mary Wortley Montagu

Murasaki Shikibu

Naomi Stead

Paul B. Preciado

Susan Renni

Publisher

Penguin Classics (2005)

Publisher

If I Can’t Dance

Volume

A Manual for Cleaning Women

Annotation

Anastasia Zharova on Dear Conchi

7 January, 2022

Publisher

P. Becket and P. A. De Hondt

Publisher

Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, Brown, and Green, Paternoster-Row; and John Murray, Albemarle-Street

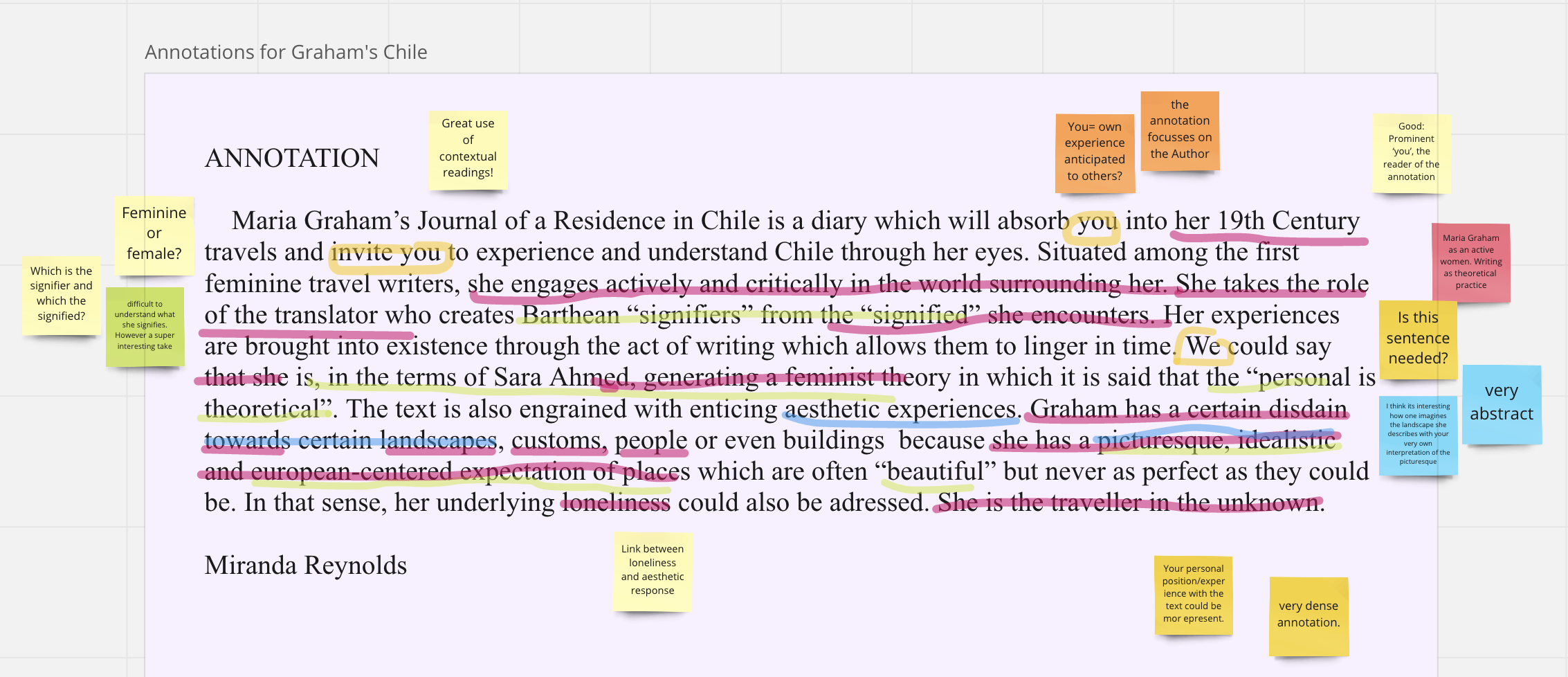

Annotation

Stefania Archilli on Residence in Chile

6 December, 2022

Annotation

Carolina Catarino Gomes on Residence in Chile

6 December, 2022

Annotation

Miranda Reynolds on Residence in Chile

6 December, 2022

Annotation

Laia Meier on Residence in Chile

6 December, 2022

On the perception of beauty in Maria Graham’s Residence in Chile

It is such accidents as these which the poetical Greeks delighted to adorn with the rich fabulous imagery which spreads a charm over all they deigned to sing of.

In Residence in Chile (1824) Graham reflects on beauty and the importance of its transmission for it to be perceived (and immortalized). By making connections to Greek mythology she asserts her own expertise and knowledge and furthermore adds to the canon what in her opinion is missing.

Maria Graham stands in the landscape of Pudaguel and compares it to the fountain of Arethusa in Syracuse: “How much more beautiful is the scenery round the banks of Pudaguel, than the dirty washing-place that marks the fountain of Arethusa in Syracuse!” Graham then notes that the difference in the perception of both places lies in the stories that we know of a place not necessarily of the place itself: Graham takes us back to the moment she visited the fountain of Arethusa for the first time, a place so dear to her imagination due to the stories told to her when she was a child that although at first she was disappointed of the scenery soon her

[…] imagination, longing from youth to see where ” Divine Alceus did by secret sluice steal under-ground to meet his Arethuse,” soon encrusted the rock with marble, and restored the palaces, and the statues, and the luxury of that fountain which once deserved the praise or the reproach of being the most luxurious spot of a luxurious city.

And in contrast:

Here Pudaguel sinks in lonely beauty unsung, and therefore unhonoured.

What Graham says is that mythologies around a place make them rise from only their material reality and imagination fueled by stories have the power to “encrust the rock with marble”, to bring ruins back in time – to make the beauty of a place eternal.

I’d like take this concept further: only what is talked about and shared, has value. Only what is sung of, is remembered and rendered immortal. Only then does it become part of a collective memory that shapes in return our society. Our references our imaginaries, how we see something and not something else. So, what Graham does in her travel journal can be seen as transformative and feminist: by announcing what stories are missing in the collective memory, she is part of, and by writing about them here, she is adding to the canon.

However, we must be aware of her own bias and imperial eyes: she is ignorant of local mythologies that might exist and only acknowledges European mythologies. Nevertheless, she is writing stories about places and therefore making them heard and remembered. She is adding her own references instead of just looking at the world through the eyes of the Writers before her and with that using her voice and her mental image to be transmitted.

The view from the pass of Pudaguel is most beautiful. Looking across the river, whose steep banks are adorned with large trees, the plain of Santiago stretches to the mountains, at whose foot the city with its spires of dazzling whiteness extends, and distinguishes this from the other fine views in Chile, in which the want of human habitation throws a melancholy over the face of nature.

Annotation

Anne Hultzsch on Journal of a Residence in Chile

12 May, 2022

Sir Thomas Lawrence, Maria, Lady Callcott, 1819

Besides contributing to art criticism and historiography, Maria Graham (1785-1842, née Dundas and later Lady Callcott) was most successful at publishing the diaries of her travels. In these, she drew on a range of registers, from aesthetic and scientific to economic and political, besides that of gender. It is this range of approaches to understanding and experiencing spaces, which makes her contribution particularly valuable to architectural historians. It demonstrates how women, barred from the specificity of the expert’s or practitioner’s role, employed expert knowledge to describe the environments they found themselves in, be these built, social, or botanical. Graham’s Chilean diary in particular shows a critical engagement with the concept of the picturesque and the construction of layered landscapes.

Maria Graham, View of Quintero Bay, seen from the place where the house was (Valparaíso) taken from the book “Journal of a Residence in Chile” (1824)

Volume

Im Gespräch 8 Positionen zur Schweizer Architektur

Volume

Im Gespräch 8 Positionen zur Schweizer Architektur

Publisher

University of Minnesota Press

Annotation

Emilie Appercé on The Problem of Speaking For Others

3 October, 2021

Text recommended to everyone, activists and non-activists alike, by the feminist philosopher Deborah Mühlebach during the reading room session organised by Annexe at ZAZ, Zentrum Architektur Zürich, on the very complex question of the practice of representing for others, a person or a group of people in one’s interest. Everyone does it. The text was originally published in Cultural Critique in 1992.

Publisher

Princeton Architectural Press

Annotation

Amy Perkins on Speaking of Buildings

24 August, 2021

My interest in alternative sources for constructing architectural historiographies came about through multiple various conversations.

Jane Hall spoke about how and why documents are preserved during the Parity Talks V in relation to her own experience with Lina Bo Bardi’s archive. Helen Thomas recommended that I look at Janina Gosseye’s research, which has since led me to other great oral histories such as Margaretta Jolly’s Sisterhood and After: An Oral History of the UK Women’s Liberation Movement, 1968–present which contains, among many other voices, that of Barbara Jones, a builder in the 1980s, who talks about her involvement in the WAMT (Women and Manual Trades), a municipal feminist initiative borne out of the Women’s Liberation Movement.

I was never really taught to question who’s stories I was listening to in my own architectural education, but knowing who gets to speak and who is listening is key to undoing patriarchal ideas of authorship and allowing those who have a hand in the making of, maintenance of, and experience of architecture to be written into its history.

Publisher

Fitzcaraldo Editions

Publisher

Ala Verlag (1983)

Annotation

Helen Thomas on Fahrten einer Paria

10 July, 2023

This annotation was written in 2021 in response to the SAFFA Growing Library’s call for commentary on books in their collection:

I have two reasons for choosing this book – Flora Tristan sounds like an amazing and inspiring woman who I know almost nothing about. I have never read one of her books, and so it would be fascinating to get an insight into her way of thinking and addressing the world. Thank you for introducing her!

Secondly, I have long been interested in Latin America, having travelled through the south on incredibly long bus journeys – including the length of Chile and the altiplano of Bolivia as a student, in 1990. I did not visit Peru though since the Shining Path were very active then, and I haven’t been back since. I would like this story of a woman travelling through this landscape, encountering its layered cultural artefacts and customs in the moments after Independence from Spain. This would provide the foundation of my own fantasised journey to this country that I hope will soon become reality.

Annotation

Lorena Bassi on Fahrten einer Paria

6 January, 2022

Escaping her violent husband and her life in France, Flora Tristan embarked on a journey to Peru in 1833 to find her estranged Peruvian family and seek her father’s inheritance to gain financial independence. Tristan returned to France in 1834 and published her travelogue of Peru under the name Pérégrinations d’une Paria 1833– 1834 in 1838.

Her position as a French woman visiting Peru and her family ties to Peruvian aristocrats allowed her to enter the world of the Peruvian upper-class and to travel around the country. The observations and critical reflections she made during this time are written in a novelesque style with her as the main protagonist. Her writing is characterized by a friction between her socialist and feminist views and her feelings of moral superiority stemming from her imperialist European background. Additionally, the image of the pariah that Tristan constructs for herself in Peru helps her to have a different gaze on the country.

The different layers of identities she takes on in her text and her shifting between them in different situations make for a travelogue which offers a distinctive view on Peru in the 1830s from the eyes of a female writer.

Publisher

Berkeley Publishing Company

Annotation

Emilie Appercé on the New Woman’s Survival Catalog

4 July, 2021

I ordered my edition of the New Woman’s Survival Catalog after watching a lecture by Mindy Seu, a designer and researcher whose work I discovered while scouring the colophon of a friend’s homepage as I was trying to build my own. The NWSC inspired her iconic cyberfeminism index—an online ever growing index which gathers techno-critical works starting from 1990 (when the term ‘cyberfeminsim’ first came into usage)—commissioned by Rhizome and now premiering at the New Museum’s ‘First Look’ exhibition.

The catalog is an impressive compilation of feminist how-to articles, wild accounts and hyper-specific tips—with themes covering ‘consciousness-raising,’ ‘women and art,’ ‘work and money,’ ‘self-defense’ or ‘homesteading.’ Some of the titles include: “Living alternatives: communal, collective, alone, with or without men and children,” “How to do your own divorce,” “Buying land,” and “Running a small farm”. Its expressive graphic style is reminiscent of self-made fanzines. The black-and-white photographs are high-contrast photocopies. Next to them are business cards and journal extracts cut and pasted next to a fleeting poem.

The authors, Susan Rennie and Kirsten Grimstad (having just graduated from Columbia University) were working on a women’s studies bibliography when they were reminded true revolutions begin beyond the walls of the institution. They embarked on a two-month road trip across the United States to discover the new woman. Five months later, they produced the New Woman’s Survival Catalog, (a feminist response to the counter-culture magazine, the Whole Earth Catalog)— a fast-paced, energetic account about the evolving consciousness of pioneering women in the early 1970’s. The revolutionary vivacity leaps off the pages. It’s not just a feminist manifesto. It’s a feminist everything. The printed-version of a feminist Google, if you will —an alternative tool for women to fulfil their changing expectations and run their own enterprises (the latter having existed all along) outside the margins of the patriarchy.

In a pre-internet era, this catalog is a sort of meeting-place, where women—from all educational and social backgrounds—could represent their definitions of the new woman in whichever form they deemed relevant (be it through farming, economic independence or DIY). I think that Susan and Kirsten, in travelling and discussing their project, may have had similar feelings as we do working on Women Writing Architecture—of wanting to celebrate women, of going on a campaign to raise consciousness about the nature and sources of their creativity. At a time when libraries were closed due to a worldwide pandemic, but online sharing resources were (and still are) blooming everywhere, this catalog (as well as Mindy’s website) acted as solid precursors for our initial discussions about this platform, Women Writing Architecture.

Publisher

University of Texas Press

Annotation

Loudreaders on El Lector

24 June, 2021

In El Lector, Araceli Tinajero traces the Cuban beginnings and describes the evolution of the loudreaders and the role of iconic figures like the Puerto Rican feminist and anarcho-syndicalist Luisa Capetillo in the tobacco factories across the Caribbean and US as they were able to establish networks of subversive solidarity that promoted emancipatory practices. Among the texts read by Capetillo and others in the tobacco factories, Kropotkin’s Mutual Aid served as a model for solidarity, collective organization, and emancipatory empowerment.

Publisher

University of Brighton

Volume

Exhibition Emotional Catalogue of Booths

Annotation

Francisco Moura Veiga on Interview with Annebella Pollen on the Typology of the Photobooth

18 May, 2021

Annebella is not an architect, she is a photography historian, researcher, and lecturer. This helps to give background to my surprise at how sharp and precise her takes on the typological analysis of photobooth are in this text. Without neglecting the sharing of the information specific to her background, Annebella expands on the formal, material, and functional aspects of a booth – the common turf of the architect – with a depth and clarity I have rarely experienced in my time as editor of architectural publications. This text was for me an awakening of sorts and remains a stark reminder of how other, non-architect eyes and voices can, at times, better see and speak about architecture.

Volume

Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture

Annotation

Anoma Pieris on Borderlands/La Frontera and Can the Subaltern Speak?

13 May, 2021

(image) Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak’s famous essay ‘Can the Subaltern Speak?’ highlighted the entitlements that guarantee visibility and vocality for some and not for others; and asked for greater self-reflexivity when writing on those without the agency to represent their interests. Her essay critiqued the Subaltern Studies Collective, a group aligned with Postcolonial Studies, predominantly South Asian scholars who explored Antonio Gramsci’s ideas in understanding non-elite forms of anti-colonial resistance. Their scholarship informed my PhD research project Hidden Hands and Divided Landscapes: a Penal History of Singapore’s Plural Society (2009), examining colonial architecture and urbanism’s reliance on transported convict labourers.

Kimberlé Crenshaw’s work on intersectionality argues that oppression occurs along multiple axes of identity – including race, class, gender, and age, for example. Identity is complex and multilayered. In Sovereignty, Space and Civil War in Sri Lanka: Porous Nation (2018), I asked if there were other ways of understanding the country’s protracted and bitter conflict beyond mutually hostile ethno-nationalist categorisations, focusing on generational structural changes that were both political and economic. Extending this idea to human displacement and diasporic subjectivities, I looked at how identity was constructed or redacted through spatial and material practices.

Gloria Anzaldúa’s Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza, was inspirational for Border-Thinking, a branch of postcolonial studies scholarship that speaks from the periphery; critiquing centralised systems of power taken for granted in architecture’s subscription to nation-building. I tested these ideas in an anthology that responded to the changed landscape of human displacement, globally: Architecture on the Borderline: Boundary Politics and Built Space (2019). Contributing authors demonstrated how the spatial disciplines might illuminate and humanise aspects of physical and political border creation through close attention to material and socio-spatial practices in border land sites.

In The Architecture of Confinement: Incarceration Camps of the Pacific War (forthcoming) co-authored with the California-based scholar, Lynne Horiuchi, we combined the above approaches in exploring how citizenship practices were altered by the war. Our argument was that the sovereign border was reconstituted through prison camps in which enemy nationals and diasporic citizens were subjected to punitive subalternisation. They were stripped of entitlements and possessions. They were selected for segregation based on reductive and racialised national categorisations which the intersectional forms of political consciousness they displayed in the camps often contradicted.

We were both interested in the deployment of unfree labour for prison agricultural and industrial projects. Lisa Lowe’s The Intimacies of Four Continents argues that after slavery was abolished, racialised indentured labor underwrote Western liberal government. Racialised prisoner labor in the wartime camps continued this illiberal practice.

The above interdisciplinary explorations suggest ways of seeing our physical and material worlds not as objects of study in and of themselves but as conduits for understanding broader questions of social justice. My intellectual preference is for using Southern Theory; theories from the Global South that examine sites and experiences of structural exclusion or oppression. The term is used in two ways: to describe economically disadvantaged regions outside Europe and North America; people or places adversely impacted by globalised capitalism; and, also, as described above, to critique the resultant racialised relations of power.

Annotation

Mary Norman Woods on Jane Drew Memoirs

31 March, 2021

Although there has been a Jane Drew Prize honouring innovation, diversity, and inclusiveness in architecture since 1998, writings about the award’s namesake are rather few in number: a tribute written by friends and colleagues on the occasion of her 75th birthday in 1986: a monograph on Drew and her partner and husband Maxwell Fry’s practice in 2014; two volumes on Drew and fellow Chandigarh architects Fry, Pierre Jeanneret, and Le Corbusier from 1999 and 2010; and a handful of articles, many about the Drew Prize winners rather than Drew herself.

However, Drew told her own story in these undated and still unpublished memoirs. The Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) holds a transcript of these memoirs with a photocopy on deposit at the Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA). Since I cannot quote from either without the estate’s permission, I can only write (I trust) that Drew’s tone is conversational as she reflects on her life and work in England, Africa, India, and Iran. Here she privileges events, people, designing, and making rather than the buildings.

Drew’s memoirs deserve a much wider audience beyond those who can travel to either London or Montreal. I hope this entry encourages the prize committee members or RIBA or CCA to approach Drew’s estate about publishing them and then commissioning introductory essays (not only from Drew scholars but also prize winners) along with drawings and photographs from the Fry and Drew Papers at RIBA. It is a publication long overdue.

The manuscripts for Jane Drew’s unpublished memoirs are located at: Fry and Drew Papers, Royal Institute of British Architects Library [under library restrictions]; and Canadian Centre for Architecture (photocopy of transcript) [under library restrictions].

Publisher

Archival papers

Volume

Burnet, Elizabeth "journals and papers" Bodleian Library, MS Rwl. D. 1092, folios 111-203 n.d.188

Annotation

Hélène Solvay on La Grande Arche

4 March, 2021

A non-fiction narrative description of the journey from conception to construction of the Parisian monument La Grande Arche de la Défense. Through a series of interviews and extensive research, the author recounts and condenses the complexity of all aspects of state-funded, large-scale architectural projects – a fragile balance between beauty, technique, politics, and finance. Cossé opposes two key characters: the poetic and enigmatic Danish architect Johan Otto von Spreckelsen, winner of the design competition, and the rigid and convoluted French administration, with its associated egos. It is both a detailed account and an evocative tale of the trials and tribulations of a grand project.

Publisher

Sternberg Press

Glossary

The following themes have been noted as being present in the citations in your collection.

-

by The Royal Institution of British Architects

If producing a building can be split into a chronological sequence of types of work and action, then the term construction defines the stage when it starts to be built. The architects and other members of the design team often work both at the building site and in the office. The Royal Institution of British Architects has defined this sequence in a document titled The RIBA Plan of Work (2020), which describes stage 5 as Manufacturing and Construction. Two more stages follow this – 6. Handover and Close Out; 7. In Use.

-

by

Women Writing Architecture

If art criticism is the analysis and evaluation of works of art, could architectural criticism be applied to specific buildings, or is the subject of critique much wider? It depends on the limits of the term architecture – which can flood into all realms of life and even be described, when freed from canonical definition, as including instances of human intervention for the purposes of living. So, if art criticism is framed by theory, as an interpretive act involving the effort to understand a particular work of art from a theoretical perspective and to establish its significance in the history of art, what could architectural criticism be? Of all the words in the glossary, critique raises the questions of why and who for? the most strongly.

-

by

Helen Thomas

This important word is laden with implications, since it is often associated with the cult of domesticity developed in the U.S. and Britain during the nineteenth century that embodies a still widely-influential value system built around ideas of femininity, a woman’s role in the home, and the relationship between work and family that this sets up. When conventional boundaries of what and who constitutes a family are questioned, so too is this fixed definition of domesticity. Within writings about architecture, this extends to the physical and spatial qualities of the domestic interior, and their socio-political meanings as they change over time and geography.

-

by

Annmarie Adams

Domesticity refers generally to life at home, often with connotations of togetherness and family. The most common examples of domestic architecture are houses and housing, though other building types sometimes include residential associations to communicate explicit messages about care and comfort. Long-standing symbols of domesticity are pitched roofs, chimneys and fireplaces, and fragrant kitchens, though these vary across cultures and geographie. Domesticity has been a focus for many feminist scholars, due to its close association with women and motherhood.

-

by

Women Writing Architecture

In this context, the term environmentalism overlaps with sustainability, with a focus on the natural environment as a system. At its simplest, to sustain means to be able to be maintained or defended, and as such requires a system within which there is something to be upheld, or sustained at a certain rate or level. With the particular economic and political meaning that this word is freighted with, the reality of any system that constitutes its context is always in flux, always in question, because it reflects the ideological position of the individual or group using it. Most often, the term is used to define the actions or attitudes necessary to maintain aspects of the world as they exist in the early twenty-first century – that the global temperature and sea levels do not rise, that capitalism can continue as the dominant economic system; but this is often given a progressive intention in advocating a change in the system and how it works globally, with an intention towards equality – providing a consistent water and food supply for all the world’s population, for example, equal access to clean energy and economic security.

-

by

Women Writing Architecture

The central tenet of this powerful word is a belief in the social, economic, and political equality of women, and it is in this general sense that it has been applied as a thematic term in this annotated bibliography. While this is a clear statement, many complexities are embodied with the ambiguity of its terms, as well as the history of its struggle. As a descriptive term, it has been broken down into various categories which vary with the ideological, geographical and social status of the categoriser. For example, feminism is sometimes assigned chronological waves or stages: from the 1830s into the twentieth century – women’s fight for suffrage, equal contract and property rights; between 1960 and 1990 – a widening of the fight to embrace the workplace, domesticity, sexuality and reproductive rights; between 1990 and 2010 – the development of micropolitical groups concerned with specific issues; and the current wave of feminism that draws power from the me-too movement, and recognises the fluidity of biological womanhood.

-

by

Women Writing Architecture

This word overlaps with other themes in this glossary – with domesticity and the sourcing, storing and preparation of food, or sustainability in a wider political and economic sense that embraces the perceived responsibilities of individuals and communities alike to produce and consume food in response to global issues of climate change, biopolitics and economic disparity, for example. As such, the definition extends out from its descriptive relationship to the objects of consumption into spatial realms of all scales.

-

by

Women Writing Architecture

Writing for children is also writing for adults, and not just those who are imminent, although it is a useful place for embedding ethical frameworks for future life and creative work, and for framing desires and aspirations. This term encompasses writing by women to be read to and by children, but also to send messages to each other, and as such can be a feminist form of writing of a type taken to powerful heights by writers like Angela Carter, Jean Auel, Ursula Le Guin and Frances Hodgson Burnett.

-

by

Women Writing Architecture

Gender is a social construct whose traditional binary construct – male/female – is challenged by the concept of gender fluidity, which refers to change over time in a person’s gender expression or gender identity, or both. Another direction in which the question of gender as a social construct is extended is into the realm of interchangeability with other species.

-

by World Health Organisation

Gender refers to the characteristics of women, men, girls and boys that are socially constructed. This includes norms, behaviours and roles associated with being a woman, man, girl or boy, as well as relationships with each other. As a social construct, gender varies from society to society and can change over time. Gender is hierarchical and produces inequalities that intersect with other social and economic inequalities. Gender-based discrimination intersects with other factors of discrimination, such as ethnicity, socioeconomic status, disability, age, geographic location, gender identity and sexual orientation, among others. This is referred to as intersectionality. Gender interacts with but is different from sex, which refers to the different biological and physiological characteristics of females, males and intersex persons, such as chromosomes, hormones and reproductive organs. Gender and sex are related to but different from gender identity. Gender identity refers to a person’s deeply felt, internal and individual experience of gender, which may or may not correspond to the person’s physiology or designated sex at birth.

-

by

Paul B. Preciado

I. To begin with, the regime of sex, gender and sexual difference you consider universal and almost metaphysical, on which rests all psychoanalytical theory, is not an empirical reality, nor a determining symbolic order of the unconscious. It is no more than an epistemology of the living, an anatomical mapping, a political economy of the body and a collective administration of reproductive energies. A historic system of knowledge and representation constructed in accordance with a racial taxonomy during a period of European mercantile and colonial expansion that crystallized in the second half of the nineteenth century. Far from being a representation of reality, this epistemology is in fact a performative engine that produces and legitimizes a specific political and economic order: the heterocolonial patriarchy.

From: Can The Monster Speak? A Report to an Academy of Psychoanalysts (Fitzcaraldo Editions, 2021): 45

-

by

Joan Wallach Scott

Most recently … feminists have in a more literal and serious vein begun to use “gender” as a way of referring to the social organization of the relationship between the sexes. The connection to grammar is both explicit and full of unexamined possibilities. Explicit because the grammatical usage involves formal rules that follow from the masculine or feminine designation; full of unexamined possibilities because in many Indo-European languages there is a third category – unsexed or neuter.

From: ‘Gender: A Useful Category of Historical Analysis‘, American Historical Review, 1986

-

by

Women Writing Architecture

A monograph usually engages with the life, and maybe also the life work of an individual. In this context, the subject is usually an architect or designer, sometimes that of a partnership or collective, which is often interpreted through the life experiences – also recounted – of the subject. Sometimes the subject is a single building or project. Usually written by one author, a monograph presents a single point of view on the subject, often with scholarly credentials through which it assumes authority. The monograph is a familiar tool for defining the importance of the individual creative figure and establishing a place for them within the canon. Until recently, the lives and works of women architects and designers have not often been the subjects of monographs, but important work in redefining the canon of architectural history has led to a series of books addressing this discrepancy.

-

by

Janina Gosseye

There are several things that can be done to expand the map of architectural history and historiography. First, architectural historians could acknowledge that those who use, occupy, and construct buildings possess unique spatial knowledge. They also could recognize that the stories that these people can tell about the everyday use, occupancy, and construction of buildings can provide different, more intimate insights into their failures and felicities, their nooks and crannies, and the social and cultural “life”. Second, architectural historiography could take a more inclusive stance vis-à-vis the narrators of architectural history, those who convey stories of and about buildings. Polyphony and alterity need not only be celebrated in the stories that are told and the perspectives that are included in architectural history proper but also could extend to those who are writing it.

excerpt from Janina Gosseye, Naomi Stead and Deborah van der Plaat Speaking of Buildings. Oral History in Architectural Research (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2019)

-

by Tisch Zwei Verein Ennenda Lunchtime Workshop, July 2023

A principal condition of living in a large settlement, a city, for example, is the possibility of anonymity, which requires any collective space – both interior and exterior – to be shared by strangers. During the workshop, we discussed the ways in which the term ‘shared space’ breaks down the distinction between private and public, which has permeated discourse around the city and urban space since the 18th century.

The concept of ‘shared space’ also bypasses the focus on functional definitions of spaces, neighbourhoods, districts and regions. Shared space embodies the prevailing power structures defined by economic, political and social factors that produce the multiple and different realities of its users – for some threatening, or controlled, for others welcoming, comfortable, unseen. So, rather than being a qualifier of functional or dysfunctional inhabitation, it is an acknowledgement of the layers of meaning that a shared space can have, ultimately in any settlement, whether a village or a city.

-

by

Helen Thomas

This word was discussed at the Tisch Zwei Verein Ennenda Lunchtime Workshop in July 2023 as a way of describing or acknowledging writing that in some way explores or challenges the centre or what is considered normal without falling into a binary definition. So the centre in whichever circumstance or characteristic is being written about is not defined by an opposite, but instead situated on a spectrum of possibility. The normal may not be in the centre of this spectrum, and in may certainly slide up and down it, get wider or narrower in extent, or even disappear all together.

-

by

Anne Hultzsch

Commonly regarded as a (more or less) personal account of a journey written in the first person, travel writing is often considered as sitting between genres, between fact and fiction, and has in the past served a variety of purposes. Trailing the history of travel itself, in the West it has undergone a transformation from those accounts reporting on justifiable travel up to around the French Revolution – religious pilgrimage, mercantile journeys, and variations of the educational Grand Tour – to more subjective descriptions of journeys openly undertaken for pleasure since around 1800. It was this subjective mode that, in many ways, opened the doors for female authorship. Often taking the form of letters or diaries, travel accounts written by women exploited the frequent male admission that the female mind was particularly suited for sentimental descriptions based on the emotional response to the foreign. There were indeed critics who ascribed women with a special sensibility (otherwise seen as weakness) rendering their descriptions of buildings and landscapes particularly vivid and captivating. Travelogues also sold well – so this was a good means to earn a living for a middle-class woman who would have struggled to take most other types of paid work while keeping her social and moral standing in society.

-

by

Women Writing Architecture

Searching for writing by women about architecture in the long period preceding the twentieth century reveals few texts in the conventional sense; that is, familiar within the form of canonical histories, theories and critiques of buildings, ideas and architects’ lives. When this is the case, a more lateral approach to the definition of architectural writing is required, and one of the fields where women, intrepid women, were writing about architecture was in their travel writing, where they recounted their experiences and impressions of exotic worlds near and far, and the buildings they found there, for their counterparts who stayed at home.

-

by

Women Writing Architecture

Initially, this term was a means of gathering together and identifying texts that refer to how we know, think and act through the senses, although this intention has been interpreted differently by the various Women Writing Architecture editors. Sometimes, it seems to embrace emotions, sometimes it seems to embrace attitudes.

-

by

Women Writing Architecture

First gathering philosophical texts by women, especially those dealing with frameworks for testing how knowledge is constructed, this term now embraces other texts. These might be referring to thinking leading to acting in a transgressive way, or at least perceived such in a hegemonic context. Another important set of texts, which are also included often within spectra and in this sense questioning what this difficult term includes and doesn’t include, are those engaging with neurodiversity and typicality.

[{"page_number":"4","note":"I love the fact that Lady Murasaki comes up first in this collection - and raises the question of whether a diary is oral history, not just because it is written rather than spoken, but also because some diaries are private. \r\n\r\nIt creates a challenge to the boundaries oral history, or the idea of history itself, which is by nature a social, a shared story. That the sharing is the quality that makes it history. \r\n\r\nThere is also the issue of the 'truthfulness' of a diary. This is relevant to oral history in general, which is presents a subjective viewpoint or memory. \r\n\r\n*****************************\r\n\r\nAnemones, like the Diary of Lady Murasaki and several of the texts in this collection belongs to a collection, in this case that of Madame ETH, collected for the Life Without Buildings exhibition. I don't know this book but it is intriguing - what is troubadour poetry? Simone Weil's work involves performance, and so again tests the boundary of oral history - speaking is a performance, how far outside the voice does oral history extend? \r\n\r\n*****************************\r\n\r\nAs for Dear Conchi, a story from Berlin's book A Manual for Maintenance Art, again its the autobiographical that makes it oral history. Maybe this is an instance of the classifying data inputter deciding? ","endnote":false},{"page_number":"5","note":"The addition of Turkish Embassy Letters and Journal of a Residence in Chile follow the same logic as Lady Murasaki's diary - the question of writing counting as speaking, if it is a record of writing directly to oneself or another person, without wider intent. \r\n\r\n*****************************\r\n\r\nThese two are interesting in that they bring early women's voices into the field of architectural history, a principal intention of Anne Hultzsch and her Women Writing Architecture 1700- 1900 (WoWA) project at ETH Zurich. The first four annotations here were produced during a workshop in Hultzsch's seminar course - Parity in History? ","endnote":false},{"page_number":"9","note":"The Annemarie Burckhardt and Beate Schnitter entries come out of an explicit oral history project that reflected on the position of eight Swiss designers, two of whom were these women. They are represented in a wider collection related to this volume by Reto Geiser that includes other texts written by them.\r\n\r\n\r\n*****************************\r\n\r\n\r\n\r\nThe Problem of Speaking for Others is very important in the context of oral history, and wouldn't be tagged or categorised as belonging to it. This underlies the idea of the glossator, with its intention to extend slightly outside preconceived definitions of terms, however lateral the intention. Alcoff's challenge and question to something which \u2013 as Emilie Apperce\u0301 points out, everyone does \u2013 causes us to reflect on our own assumptions and unconscious bias.","endnote":false},{"page_number":"10","note":"Speaking of Buildings is a ground-breaking volume of collected essays around different aspects of oral history in the architectural discourse, interesting in that it brings to the fore voices not conventionally heard (but different to the ones Hultzsch is listening to). These include participants in the construction and briefing process.","endnote":false},{"page_number":"11","note":"Adding Paul B Preciado's essay Can The Monster Speak is perhaps stretching the definition of oral history a lot, but the issue of speaking from an ostensible edge, and of speaking from that other centre (rather than being spoken for) makes a purpose and meaning for it that has a great deal of potential.","endnote":false},{"page_number":"12","note":"The New Women's Survival Catalog with its great variety of content has many descriptive categories attached to it. I like the way Sarah Ahmed's How to Live a Feminist Life is an echo closer to our own time.","endnote":false},{"page_number":"14","note":"Loudreaders as a group, their name in itself, brings into focus the issue of reading through speaking, making text into an action. El Lector, the reader, magnifies that idea.\r\n\r\n\r\n\r\n\r\n\r\n\r\n\r\n\r\n\r\n\r\n\r\n\r\n\r\n\r\n\r\n\r\nAre interviews oral history, since they are staged speaking?","endnote":false},{"page_number":"15","note":"\r\n\r\n\r\n\r\n\r\nAn important edge to the idea of oral history, the human voice telling a situated story, is one of the many reasons why this text, Can the Subaltern Speak - is a central, disruptive text in this collection. In this context, it highlights issues around who is invited to speak and where they are speaking from. These are both abstract in sense - the centre, the edge etc, but can also be imagined in specific spaces: the community hall versus the gentleman's club, a bench on the street as opposed to the archive reading room or state radio station ... So many facets come alive in the imagination: language and dialect, education and confidence (and entitlement, as Anoma Peiris points out), received and first principles.","endnote":false},{"page_number":"18","note":"\r\n\r\n\r\n\r\n\r\n\r\nThis citation, suggested by Mary Norman Woods, is an unpublished manuscript in an archive. Woods tells of instances when Jane Drew has been spoken about and points out that the estate controls the dissemination of her voice itself, which can only be heard, or read, by one researcher at a time. It speaks not for itself but through the person who reports on it. The voices of this and other women locked in archives, often in the interstices of the archives of male protagonists, have begun to leak out though.","endnote":false},{"page_number":"19","note":"\r\n\r\n\r\n\r\n\r\n\r\n\r\n\r\n\r\n\r\n\r\n\r\n\r\n\r\n\r\n\r\n\r\n\r\n\r\n\r\n\r\n\r\n\r\nLa Grande Arche gives us an unusual first-person insight into a women building, a rare and valuable combination of woman, construction, oral history.","endnote":false},{"page_number":"23","note":"\"Oral history is as old as history itself and might be considered the first kind of history. The intensive modern use of oral history is, however, relatively new, certainly when it comes to the historiography of modern architecture.\" Quote from Janina Gosseye's call for papers for her guest edited editions of the journal Fabrications.\r\n\r\n\r\nGosseye can be seen discussing oral history in architecture\r\n at: https:\/\/www.youtube.com\/watch?v=HCR1QB9zZZo","endnote":true}]