Share this Collection

1 Citation in this Annotation:

Annotated by:

Maria Lederer on Interiors: nineteenth-century essays

21 November, 2023

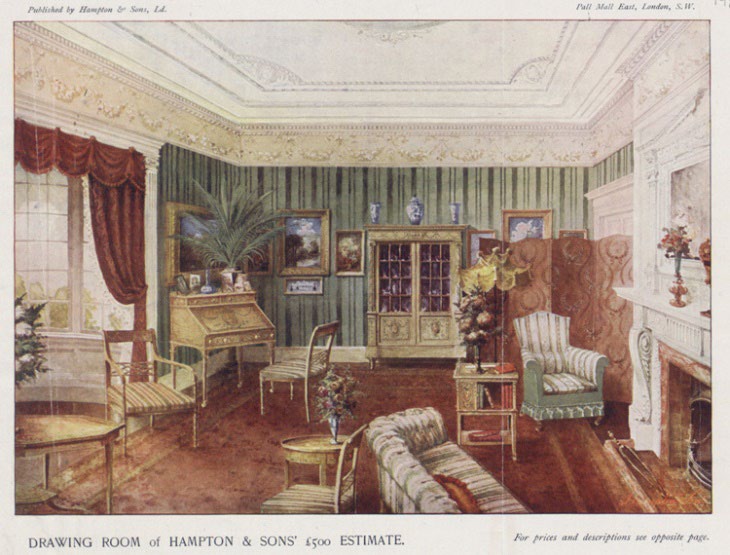

In a feminist review by Juliet Kinchen, “Interiors: nineteenth-century essays on the ‘masculine’ and ‘feminine’ room” unpacks the constraining gender normalities that existed in the Western world for users of the home. The author initially states that the home represents the “antithesis of public space” (Kinchen, 13), an environment in which women, the assigned decorators of the home, were allowed to politely express themselves in a way that conforms with masculine and feminine social understanding of the time. Each room type was expected to be codified by function, and decorated in a way that reflected the expected gendered behaviour in each programme. Some of these assumptions began in the home’s front foyer, where one would enter and receive an impression of the family’s dignity. These judgments were gauged by the level of grandeur and quality of materiality (Kinchen, 14). Throughout the home, materiality, iconography, shapes, and scents were utilized to pair the gendered functions within each room. The drawing room is one of the first rooms transitioning from the main hall, often representing the “taste and values” of the women in the home. Like a shopping window, the room often functioned as a setting for unmarried daughters to interact with potential suitors, a place of performance to prove good morals and femininity. Often an axis between nature and feminine values was coupled together, using flora, fauna, and bright hues to communicate this “lightness and spiritual purity” (Kinchen, 23)

As the transition continued from public to more private spaces, one would circulate into the dining or library spaces. These rooms were associated with the masculinity of the home, with the use of wood, leather, and dark shades. These spaces would be used for their intended functions such as eating and studying respectively, but secondarily for men to discuss “complex” topics, where women would then withdraw to the “drawing” room to engage in “smaller affairs” (Kinchen, 18). Ironically, if design errors were found within these masculine spaces, such as the lack of symmetry in the dining room, this would reflect negatively on the decorator of the home and her “intellectual capacity” (Kinchen, 20). Nowhere in the home would men be subjected to this objectification or level of scrutiny of their capabilities. In this way, Kinchen argues that women were woven into the interiors of these spaces as objects themselves, metaphorically and literally as the decor would often be expected to compliment their physical complexions. In the later 1880s and onward, more progressive movements were seen in interiors by toning down the decorative iconography and blending the boundaries of gender through reductive aesthetics, as seen in examples by Margaret Macdonald and Charles Mackintosh (Kinchen, 25). Interiors since then have gone through many transformations, yet the gendered origins of this spatial programming can still be seen in today’s contemporary floorplans. This reading allows the audience to recognize the connection between the floorplan hierarchy and the benefits of the patriarchy. If we are to design feminist interiors in the future, will this eliminate the hierarchical floorplan and association with gendered iconography altogether?