Share this Collection

3 Citations in this Annotation:

Annotated by:

Joana Ribeiro on Casas com nome

15 June, 2025

Together with illustrator Mariana Rio, Portuguese architect Joana Couceiro co-created the children’s book collection Casas com nome (houses with names), published by Circo de Ideias. These books are based on Ana Luísa Rodrigues’s doctoral thesis, Habitabilidade do espaço domoméstico : o cliente, o arquitecto, o habitante e a casa (The habitability of domestic space: the client, the architect, the inhabitant and the house).

In her thesis, Rodrigues places the house at the centre of a triangle: the client who commissions it, the architect who designs it, and the inhabitant who lives in it. Her aim is to understand how each of these people influences the creation of the house, and how their relationship with it shapes the way it is eventually inhabited. The house is not seen as a neutral shell, but as a responsive and contingent structure, shaped by and shaping the lives it accommodates. Habitability, in this sense, is not a fixed condition but a lived and evolving one – the result of negotiation, projection, and appropriation.

In Casas com nome, the house takes on an anthropomorphic character.

Despite telling real stories, these books are inhabited by houses that gain a life of their own: houses that are machines, houses that are dreams, houses that are inside and houses that are outside. Houses that are people,

writes the publisher Circo de Ideias. But while the house

gains a life of its own,

the life of the inhabitant is subtly displaced, or at least diffused, into metaphor. Turning the house into the main character, transforms the complex relationships described in Rodrigues’s thesis into stories that children can understand, where the tensions between architect and client, or between design and everyday life, are softened.

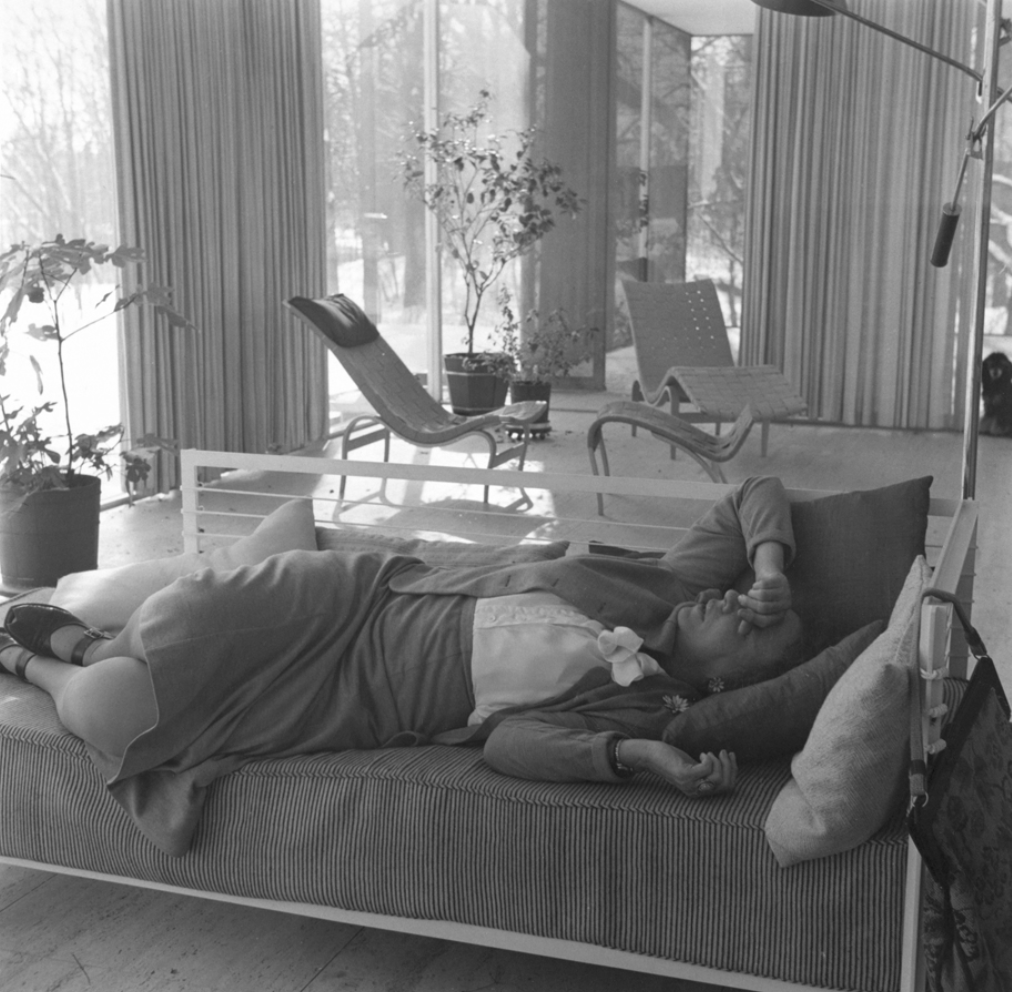

So far, Couceiro and Rio have adapted two of the houses Rodrigues selected to study: the house of Mr Malaparte and the house of Dr Farnsworth. In Rodrigues’s work, these two examples highlight conflict – between Malaparte and the architect Adalberto Libera; between Farnsworth and Mies van der Rohe. In the illustrated stories, tension is reimagined. Malaparte’s house becomes a strong and independent voice. Farnsworth’s house accepts its fragility, but doesn’t dwell on its discomfort. What in the thesis is analysed through evidence and critique, in the books is felt through the rhythm of the narrative and illustrations.

Both books playfully introduce architecture culture to children, with stories that unfold with thoughtful rhythm through a duality between full spread illustrations and free verse on white background. The verse is written in the third person, in the present tense, with a quick tempo and some repetition, that is crucial to captivating little ones’ attention. The illustrations contribute to the imaginary world created and introduce architectural representation tools such as plan, elevation and axonometric. Each book so far has distinct colour palettes that reflect the mood of the story and the materials of the building and its context. In Malaparte’s the blue of the water is juxtaposed by masonry red; and in Farnsworth’s the green context superimposes the white of the building, emphasising the narrative of transparency, of the aquarium.

The collection is originally written in Portuguese, though the second title has since been published in English. I write this annotation having only read the Portuguese versions to my daughter. The experience of reading aloud, navigating the rhythm of the verse, pausing on certain words – allowed me to engage with the text in an unexpectedly layered way. My interest in this collection has grown alongside my own transition into motherhood, which has rekindled a connection with childhood – both my daughter’s and my own. Reading these stories with her has opened up a more instinctive way of looking at architecture, less analytical and more embodied.

In Casas com nome, architecture is not simplified – it is made accessible. The books translate Rodrigues’s complex reflection into something felt rather than analysed. While simultaneously stimulating children’s sensitivity to their own environment.